Seventh of a series of posts about 100 great comics pages.

Links to: an introduction to the series; an index of posts by creator; an index of posts by title.Some things are so titanically great that we can even loose sight of how amazing they truly are: living for too long in their shadow, we come to underestimate their size. Such is

Watchmen which, despite being widely acclaimed as one of the greatest graphic novels of all time, despite being seen almost universally as the definitive deconstruction of the superhero genre, despite its widespread acclaim even beyond regular readers of graphic novels,* is somehow nevertheless continually underestimated -- because it is taken for granted, I think.

Typically in this series -- at least thus far -- I give a brief introduction to the works from which I am presenting a page, since I assume that they won't be familiar to (at least some of) my readers. I shan't do this with

Watchmen, since I presume it will be familiar to most of my readers, at least by reputation if they haven't actually read it. If not, well, the footnote below (*) will give you some indication of its cultural place in the developing field of the graphic novel; and since I am writing about the first page there's no context you need. (And I hope that this one page can convince you to read on: it is a truly wonderful book, one I recommend without reservation to everyone (so that, for example, many superhero comics require being a fan of that genre to enjoy (or even familiar with the specific characters and backstories used), this isn't true at all of

Watchmen: you can read it without liking Superhero stories and still enjoy it tremendously, as I know from several successful recommendations (and reports by others of many more.))

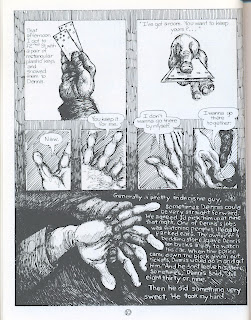

So we'll jump right into page one:

(That scan, by the way, is from my old copy of the trade paperback, bought fairly soon after it first came out. Apparently the recently-released, oversized hardcover,

Absolute Watchmen has completely re-done color (

by John Higgins, who also did the color the first time around). But since I've only seen it shrink-wrapped in the store, I can't speak to that point personally. (Though if anyone feels moved to buy me a $75 book as a present, I will not only update this entry, but I'll provide a new scan of page one.))

We open with a long upward zoom -- a shot that allows us to slowly take in a scene in every sense -- both broadly, introducing us to a city which (if we look closely) we'll see is altered from the familiar world that we know (

Watchmen occurs in an alternate history which includes different technology than in our world); and narrowly, showing us a specific scene which we come to realize (on pages two or three if not on page one) is actually a murder scene. The page's zoom actually begins with

the cover of the first issue -- in fact if you (unlike I) bought the right edition, it actually begins even earlier with

the cover of the entire book; in its day,

this cover, and its use as (effectively) the first panel of the story was atypical for (at least mainstream) comics, the first of dozens if not thousands of innovative uses of the medium that Moore and Gibbons would debut (or in some cases popularize) in their work.

So let's begin by simply noting that as an overall visual organization of a page, it's extremely striking. A zoom from a close-up street to a high-window: what a wonderful way to begin! The zoom allows us to take in the scene in a visually engaging way, one which engrosses us in the story through sheer force of receding point of view. The page, of course, is drawn with Gibbons's typical clarity and grace: he simply draws extremely clear, powerful precise art, wonderfully framed and richly detailed -- from the cracks in the sidewalk to the reflections in the building's glass windows. -- Look at the detail in the image of the street-cleaner in panel three: as far as I can remember, a character who never appears again, but one that is unquestionably

himself, a recognizable and specific individual (so that if he

does reappear, we'll recognize him). And he is extremely expressive too: from his posture and expression in this and the following panel, we can ourselves imagine a whole dialogue of his yelling at the doomsday sign-carrier who tromps unconcernedly through a sidewalk of spilt blood.

And ah yes, the sign carrier: he we

do see again: in fact, he is one of the major characters in the work. I shan't say who he is (since I imagine some of you have never read the book, and I don't want to spoil the surprise), yet while we could imagine him as incidental -- simply a passerby to represent many, and to track symbolic blood across the still-clean part of the sidewalk -- nevertheless he

isn't incidental, and indeed upon rereading a few additional connections will be made from the fact that yes,

he is here, there, on this page. This is another way in which this page -- and

Watchmen more generally -- is extraordinary: the detail and precision in the art allowing the extraordinary use of significant background characters, places, actions, so that more is always going on in a panel than one notices at first.

And I should mention that the central image that begins the zoom -- the smiley face with the blood streaked across it -- is itself an unforgettable image, a powerful reversal of a familiar iconic form: one that for me, at least, totally changed the entire meaning and set of mental associations with the smiley, so that I can now hardly see one without imagining blood streaked across it. The vapid, insipid cheer that the smiley represents has become streaked with blood, a far more arresting (if far more cynical) icon.

And, of course, one that is in many ways symbolic of what

Watchmen does on a larger scale: takes the vapid, smiley-face genre of silver-age superhero comics and drops a bit of blood on them, making them deeper, darker, more disturbing -- and unreadable again in their earlier, naively and simplistically optimistic form. This is true at almost every level, from the overall meaning of "superhero" and what they're like to the specific associations of the smiley itself (the blood is not the only thing that stains it in this work: its associations do too). It is as appropriate an image to begin with -- whether as a first panel, as the cover of the first issue, or the cover of the book as a whole -- that one can imagine.

And then there are the words.

Moore is a writer whose words are as rich and interesting as those of any contemporaneous** prose writer you care to name. This is true of his words on this page too, and even if one separates them from their images:

Rorschach's Journal. October 12th, 1985: Dog carcass in alley this morning, tire tread on burst stomach. This city is afraid of me. I have seen its true face. The streets are extended gutters and the gutters are full of blood and when the drains finally scab over, all the vermin will drown. The accumulated filth of all their sex and murder will foam up about their waists and all the whores and politicians will look up and shout "save us!" ... And I'll look down and whisper "no."

Now of course this is prose of a certain type: Moore is aping a particular style here, so it is missing the point as completely as possible to say that the prose is overwrought or hysterical: it's

supposed to be, that's the entire idea. Moore is drawing a portrait with a first-person narrative style, a portrait of a person who is overwrought, hysterical and (as we shall learn) given to right-wing anger and tempers in a John Birch society mode. (This association of a superhero -- we don't know yet, but we soon learn that Rorschach is a superhero -- with this sort of right-wing craziness is part of Moore's larger critique of (and rereading of) the genre: with murder (what we imagine Batman and Spiderman to be concerned about), Rorschach places "sex" -- immediately making us ask precisely what superheroes are supposed to be fighting, what they are defending, and who they are defending against.)

What's amazing about Moore's prose here is, given that it

is a deliberately overwrought piece, how much

better it is than it needs to be. There is a particular style of writing with a long tradition (from Shakespeare to Nabokov and beyond) in which the dialogue is placed in the mouths of characters is not only indicative of character but is also simply a bit more literary than such characters would use in real life: realism is sacrificed, to some extent, to poetry. And that's what Moore is doing here. The economy of the initial image ("Dog carcass in alley this morning, tire tread on burst stomach") is matched by the wonderful employment of sounds: the repeated staccato sounds adding to the atmosphere of menace. This is a sentence that works both rhythmically and in terms of its specific internal sounds. The page as a whole uses verbs that are -- while never departing too far from the style Moore is trying to achieve -- beautifully economical and apt: "scab over", "foam up": you can always count on a murderer for a fancy prose style, I suppose, but most won't do it this

well. Moore can, and does.

The opening quote from Rorschach's journal is apocalyptic, and heightens the tension that we already feel in our upward climb; it is characterization, beginning to play already on some of the themes of the work; and it is, in its own way, poetry.

(One more brief note about the words here: isn't "Rorschach" a sublime name for a superhero? Of course the story of his costume, his mask, his ideas (all told in chapter six) are what make it as rich as it is. But even on its own terms, it is a wonderful twist on all the simple, iconic names -- "Flash", "Spirit", "Hulk" -- that we are familiar with. This sounds like one of them -- it's plain and simply a

cool name -- while also being a reference to deeper issues of interpretation and meaning.)

Now let's talk about the interplay between the words and images.

The central technique of

Watchmen -- one that Moore and Gibbons use over and over, in a plethora of ways -- is the ironic juxtaposition. They will interweave two scenes so that each comments upon the other, so that the text of one is given new meaning by the images of the other. They will cut from one moment to another which entirely rewrites its significance. And so on. A lot of this is the sort of thing that

only comics can do -- a switching back and forth that would be so quick as to be sea-sickening in film, say. This is particularly true when Moore and Gibbons will interweave two scenes, which we don't see here; but we do see the first usage of the technique of the ironic juxtaposition, which allows to elements -- in this case, the opening visuals and the unrelated (at least in any overt sense) text that are put over them -- to comment upon each other, adding and changing the meaning we see in both.

Here are some examples of the wonderful synchronicity which Moore and Gibbons weave in the words and images: the phrase "its true face" is matched with the bloodied smiley face in the first panel; the comments about blood in the gutters in the second is literally illustrated (despite the words being written separately from what we are seeing: the words aren't describing or illustrating the scene); the phrase "followed in the footsteps" in the fourth panel occurs simultaneously with the bloody footsteps of the sign-carrier who has just walked through the blood; and so on. Above all, the text of Rorschach's journal is filled with metaphors involving looking over a chasm, which interplay with the fact that as we read we are looking from an increasing height: "the whores and politicians will

look up and shout "save us!" ... and I'll

look down and whisper 'no'"; "they... didn't realize that the trail led

over a precipice until it was too late"; "And now the whole world stands

on the brink, staring down into bloody hell..." (all emphasis added). And that last one does double duty, of course, since the watcher (who we see in part -- his hand -- in this panel for the first time) is literally staring down into blood: the blood of the murder victim thrown from the top of the view (at the bottom of the page) to die in the gutter where we began.

All these juxtapositions are fairly light, compared to ones that will come: but they set up the technique -- and, most of all, they set up the final one at the bottom of the page, the one that adds the sting at the end of the tail of this astonishing opening.

The ultimate juxtaposition is between two disconnected (in any overt sense) sets of words: the ending of Rorschach's journal and the seemingly (and misleadingly) banal line from the detective looking down where his victim fell. The juxtaposition here is between Rorschach's word-painted scenario in which "the whole world stands on the brink staring down into bloody hell... and all of a sudden nobody can think of anything to say" and the (visually portrayed) fact of a person literally standing "on the brink" of a "precipice", "staring down" -- into blood, if not hell -- and

finding something to say: namely, "Hmm. That's quite a drop". The romanticized, operatic roar of Rorschach's language is deftly undercut by the detective's simple (almost simple-minded) observation.

Because the detective is literally doing what Rorschach is describing -- because we see him doing it -- his words become an

answer to Rorschach's challenge. It is an answer that parries with the ordinary, the mundane, the non-superheroic, Rorschach's histrionic panic. The world of grand drama is made silly by the world of ordinary life (again, a symbol for the effect that Moore and Gibbons's work will have overall.) The necessity for dramatic solutions -- the existence, even, of such (over) dramatized situations -- is undercut in a line that is (if you really think about it

as an answer) quite funny.

What do you say when staring down into bloody hell? "That's quite a drop." What else?

And all of a sudden the dramatic storms, the apocalyptic warnings, that superheroes live on become to seem silly, excessive -- unnecessary. And because, in

Watchmen, the power of superheroes functions as a metaphor for power in general -- above all, political power -- the dramatic storms and apocalyptic warnings of politicians and pundits come to seem silly, excessive, and unnecessary: and we begin to think that we might not need to look up at anyone and cry "save us" after all.

Watchmen was created at the very last moment when the Cold War could still be taken seriously as an ongoing concern: it is a piece of Cold War fiction, but one which (like, say, the film

Dr. Strangelove) is a strong enough piece of work, and one with enough meaning, to survive the extinction of its original historical context. So the apocalyptic cries which Moore and Gibbons are undercutting here specifically are those of the cold war: the idea that a catastrophe is needed to end this particular looming danger. But since so much Cold War rhetoric has been transferred, with only minimal alterations, to the so-called War on Terror, Moore and Gibbons's ironic dismissal of operatic panic from the holders of power might just as easily have been created today.

Watchmen is never only one thing. It's a deconstruction of the superhero... and also a comment on the realities and corruptions of (political and other) power, using the superhero as a metaphor for the powerful. It's a superhero story... and a mystery and an alternate reality story and a series of character sketches. As I hope I have demonstrated for this page, at least, it is a work that richly repays multiple rereadings. If you've read it, but it's been a while, it's probably a better work than you remember; if you've never read it, and do, you'll find that it's just as good a work as you imagined and hoped.

Visually, verbally, and the interplay of the two... in every way, this is a great page, a terrific opening, that encapsulates many of the themes and techniques that give

Watchmen as a whole its enduring power. A great page: and the rest,

every single one of the 384 of them, are

just as good.

We see masterworks from afar -- blurred by the distance of memory and the inadequacy of our own readings. Which is why they are so often better than we remember. Better than we can imagine. Underrated. As, despite its near-universal acclaim, I find

Watchmen still to be.

----------------------------

* The first graphic novel boom of the late 80's and early 90's was ushered in by the coincidental appearance of three titanic works in a single year (1987), each extraordinary, and so astonishing in their collective power as to force themselves into broader public consciousness.

Watchmen was one, of course; the other two were Art Spiegelman's

Maus (which will be the subject of a later post in this series) and Frank Miller's

The Dark Knight Returns. At the risk of the disdain of

people whose opinions I respect, not to mention a host of irritated commentators, I'll admit that I think that

The Dark Knight Returns was, quite clearly, the weak link in that particular trio -- the Crassus to the Pompey and Caesar of that particular triumvirate. It was quite good, but not nearly

as good as the two works it was most commonly linked with. In any event, the three books catapulted the graphic novel into the public consciousness -- only to have it dwindle (

as Paul Gravett as written) once the lack of readily available other works of equal quality became apparent. By the time of the second graphic novel boom -- circa 2001 to the present -- enough older strong works had been reprinted, enough foreign strong works had been translated and a cornucopia of new strong works were being written, so that it was sustainable. But the ongoing power (of at least two of) those three works of 1987, their near-universal reputation, has in some paradoxical way almost obscured how truly amazing they actually are. (I think this is true despite the recognition the work has gotten, such as

Time Magazine listing it as among the 100 best novels since 1923).

** Comparing great writers of the present to great writers of the past is a mug's game: it

always comes off sounding ridiculous, in part because the names of old great writers come to refer not only to their specific works but to iconic notions of greatness, so that to say that

anyone is as good as Dickens or Shakespeare comes to be practically a contradiction in terms, since what "Dickens" and "Shakespeare"

mean is "writing as good as it can get". So defenders of current writers are well advised to stay away from old masters (never wrong about suffering) in their defenses.

So I won't hold up Alan Moore to anyone from an earlier era, to praise or damn him: it's simply a silly and invidious comparison however one tries to make it turn out. But I will say that, Alan Moore is in the first rank of wordsmiths as compared to any writers

of his own time that you care to name. And that's all one can ask of anyone.