I have now twice been asked in emails about the self portrait that I use on this blog (look over in the sidebar -- it's right at the top), so I figure perhaps it is worth answering here in case anyone else is curious.

The picture is a photo I took of myself in a mirror altered through the Perception Laboratory's Face Transformer, which you can play with by clicking the link. It's a little java script that transforms faces in uploaded photos. Most of the settings are about changing the race, sex or age of the subject, but a few adopt certain artistic styles -- the available ones are Botticelli, Modigliani, El Greco and then "manga cartoon" (as a general style). There's also a "drunk" setting and an "ape-man" setting that makes a sort of Planet-of-the-Apes like picture. The picture I use of myself was transformed with their program using the "manga" setting.

Frankly, the results from the transformer are hit-and-miss -- and far more often miss than hit. Most of the race/sex/age transformations aren't remotely convincing, although occasionally you get one that's not half bad. The artistic ones are fun -- but most of the results come out looking fairly similar: the base photo is often largely obscured by the transformation. (You can see why if you upload something that isn't a face and try the transformations on it.) But sometimes it works -- the right photo with the right setting can produce a fun result. It's certainly a lot of fun to play with -- a great time waster. I liked the manga version of that image of me -- I thought it looked almost like an actual manga drawing -- so I use it.

If you're interested, a larger version of the same picture can be seen here -- but I think that the close-up actually doesn't work as well: the seams show. (A commentator on the site where the larger photo is hosted said that it's "the most frightening flipping thing I have ever seen.") So just as a general effect the smaller one works better. But the larger one is interesting if you're curious about how the transformer works, since you can see the original image under the transformation.

Unrelated Afterthought: While I'm engaging in meta-blogging, I'll note that, with this post, March 2007 has just tied July 2006 as the months in which I've posted the most entries: 20 each. (My average over the lifetime of the blog is 11-12 a month.) And the latter included four posts which were just posting someone else's writing -- letters from my sister-in-law, from when she was trapped in Beirut during the July War. (On the other hand, last July the posts that I did write included several of my favorite posts to date.)

A reality-based blog by Stephen Saperstein Frug

"There is naught that you can do, other than to resist, with hope or without it. But you do not stand alone."

Saturday, March 31, 2007

Friday, March 30, 2007

100 Great Pages: Luigi Serafini's Codex Seraphinianus, page 39

Fifth of a series of posts about 100 great comics pages.

Links to: an introduction to the series; an index of posts by creator; an index of posts by title.

When I began this series, I made a list of the first few entries I wanted to do and a large number of other works that I wanted to get around to eventually. But I always knew that happenstance would play a major part. In the case of the Codex Seraphinianus, created by Italian artist Luigi Serafini, the chance was my discovering (via Eddie Campbell) that it had been posted online, in its entirety, as a Flickr set.

I described the Codex in my earlier post, but to recap briefly: the Codex Seraphinianus is a fictional encyclopedia, presented as if it was an alien artifact: written entirely in an undecipherable alien script, with strange and hallucinogenic illustrations throughout the text giving glimpses of pregnant, elusive meaning. Whether it is supposed to be from an entirely alien world (in which case the obvious people sometimes included are puzzling), from an alien looking at our world (in which case the obviously fantastical lifeforms, places, etc, are puzzling), or something else, is unclear. It's a masterpiece of suggestive mystery, of meaningful nonsense. Like many people, I first heard of it from an off-hand comment in Douglas Hofstadter's Metamagical Themas; but until its recent posting I had only seen the various sample pages available here and there on the web, and had never read it in its entirety (as it is rare and quite expensive). Having actually read it, I knew I had to include a page in this series.

But have I in fact even read it now? In my earlier blog post about the Codex, I wondered whether the word "read" was the proper word to use in discussing it. I have looked at every page -- some for longer, some for less time: the text-only pages -- at a very rough guess, perhaps a fifth of the total -- are, obviously, particularly unrewarding; many of the heavily illustrated pages are so beautiful that they took my breath away. I have never used hallucinogens, but looking at the Codex makes me feel as if I know what LSD must be like. But have I read it? Is "read" the right word?

I have come to the conclusion that it is not. This is true even though I would without hesitation say I had "read" a silent comic like Peter Kuper's Sticks & Stones or Evan Drooker's Flood. The reason is that in the context of a work like the Codex, "read" implies something untrue -- that one has actually read the existent text and not simply looked at the images. Given that the text is, so far as anyone knows, nonsense (but see here), this is impossible; but to say, "I've read the Codex Seraphinianus" implies a mastery which is unwarranted. Further, while the pages are definitely better seen in sequence -- you get a lot more out of it approaching it as a whole work, with a given order,* than simply looking at any given sample pages (said the man writing a series of blog posts about pages taken out of context) -- you don't quite read the images the way that one "reads" (by which I mean something like "performs closure on", to use McCloud's term) silent comics. Say, therefore, that I have "looked through" the Codex: it will be more accurate.

In fact, since I have announced this as a series of great comics pages, including the Codex begs the question of whether it is comics or not. Now Eddie Campbell would argue vehemently that these categories are reductive: that one shouldn't care whether or not the Codex is comics -- one should simply care that it's good. And on many levels I agree with him. But since I disagree with him on equally many levels -- and since I don't want to try to weigh in on The Great Campbell/McCloud Debate™ now (though I may at some point in the future) -- I'll simply note that the page I'm discussing happens to be a page of comics, at least by the Eisner/McCloud definition of comics as "sequential art".** A few of the pages have sequences of art that are clearly meant to be read as temporal sequence -- i.e. are comics by the Eisner/McCloud definition -- but this page is rare in being dominated by a lengthy, comics-like sequence. I think the only other one laid out in quite so traditional a comics fashion is page 41 -- two pages later. (What that means I don't know, although the pages are thematically quite similar in a lot of ways.) So even if you won't call the Codex comics in its entirety -- and I pretty much wouldn't -- I think most people would agree that this page is comics.

Anyway, it's wonderful, and from a wonderful book, so bollocks to the definitions.***

So here is page 39:

I've rotated the image 90 degrees so that its (apparent, to us) proper orientation is up -- as one would, presumably, rotate the book if one shelled out the money to have a dead-tree copy in one's hands -- but if you want to see what it looks like in the book, click here.

In many ways, the "story" here is readily comprehensible -- although the story one gets out of it is distinctly surreal. In the first panel, we are shown a map (its status as a map made clear by the labeling, in the now-familiar alien script, which is on it); in the second through fifth panels we are shown rains, followed by the growth of some sort of crop; in the sixth panel, we see the crop harvested; in the seventh, we are shown in close-up what the crop is: ball-point pens, which grow in the manner of tubers; and in the final panel we are shown the use that these are put to: they are used as the components of necklaces.

(Page forty-one, which as I said is very similar in structure, shows the growth of chairs -- not as parts then manufactured, but as full chairs -- which are then sat on by (for some reason) someone wearing ice-skates.)

It's worth noting that this is hardly the strangest page in the book -- indeed, its very nature as comics makes it among the most straightforwardly comprehensible. Nevertheless, its combination of real and imaginary features, its reordering of the familiar world in a strange way, makes it (in many ways) quite typical of the Codex.

But what are we to make of this presentation? Is the Codex describing a world in which this actually takes place? Or is this the misinterpretation that an alien culture has of our world? Or is it supposed to be metaphorical -- about creation having its roots in the earth, and hanging like a chain about our necks? -- Further, is this an answerable question -- that is, if one studies the Codex for long enough, can one figure out where and when it is supposed to document? Or is it just an exercise in defamiliarization, a playful romp in the gardens of the strange? (If ever there's been an artistic object which aims for, and achieves, defamiliarization, it's the Codex Seraphinianus.) I don't know the answer to any of these questions: I enjoy the page as an exercise in dream-like strangeness, but I don't know what to make of it.

In discussion at Eddie Campbell's blog I said that the Codex as a whole reminded me of Jim Woodring's Frank, in its eerie, often-unsettling, dream-like (or hallucinogenic) tales which mix the familiar and the strange. A commentator, "John C" (who I think is the same John C who wrote perceptively about the Codex here) replied that he thought "it most closely resembles European fantasy works like those one sees from Roland Topor and various bande desinée artists rather than people like Jim Woodring." I'll stand by my Woodring thought, though I admit that it may well have as much to do with my limited frame of reference than anything else. (Jacek Yerka also strikes me as similar in spirit.) Overall, obviously, the dominant mode is surrealism; beyond that, I don't know.

Let me take one small topic: the alien script. What is it doing in this page? Well, it changes the viewpoint: it makes what we see a representative example rather than a specific incident. It implies a whole society -- that this is a tradition, a habit -- rather than, say, some strange specific incident in which pens happened to grow like tubers in the ground, and we had so many of them that we made necklaces. The script (along with the greater context) even helps establish a narrative voice -- one of detached description -- that we then read as the intent behind the pictures. We might be wrong about that voice: it's how encyclopedias that we know are written, and might not really apply to the Codex at all, given that its supposed to be alien. But I think we tend to impute that tone to the Codex, fairly or not. And, of course, once one thinks of the Codex as a product of an alien society, we realize that we are imputing to it all sorts of things that might be wrong: even the idea that the squiggles in question are a script (with an implied language and meaning behind them, even if we can't know them) -- and not, say, simply decoration, or their portraits of the strings of which matter is made -- is simply an assumption that may be wrong. The alienness of the Codex necessarily destabilizes all our attempts to bring meaning to it (although, at the same time, we can hardly help doing so.****) There's no question that the script is absolutely essential to the feel and nature and meaning (whatever that is) of the Codex -- even if we do skip by the all-text pages quickly (for what can one make of them?), their presence is important in helping shape the meaning of more heavily image-based pages such as page thirty-nine.

Surely it's important that this page (and its cousin, page forty-one) are in the "flora" section (again, see my first footnote below), which consists of drawings and sketches and diagrams and so forth of plants. It shapes how we feel about the page; but I don't think it makes it mean any one thing.

Is asking about its meaning just silly? Is it all just supposed to be beautiful and strange? Or, on the other hand, are we missing something big if we just groove on its strangeness rather than seek more specific meaning (it certainly seems set up to encourage us to do the latter).

Did I mention that the art is beautiful?

And what are we to make of the watch in the penultimate panel, the one where we see the man holding the tuber-pen out? That's a very modern-looking wrist-watch.

Is it comics? Have I read it? What does it mean? I don't know. But I know that it's wonderful. (Can I know that without knowing what it is or what it means? I think so, but it's a funny situation to be in.) Go take a look and see what you think.

Update: Nothing to do with the Codex, but Eddie Campbell (whose name I took in vain above) and I are hashing out issues of definition in the comments. Worth a look.

___________________________________

* The Codex is quite distinctly divided into eleven sections, each with a title page, introduction and table of some sort (a summary? a table of contents?) before the main matter. Further, the rough subject of each section is fairly clear (various different attempts to label the sections come out quite similarly). And each section gains in coherence if looked through all together in order -- although admittedly not by much.

** I think that there are three major definitions of comics/graphic novels in play right at the moment. The first, which I think of as the Eisner/McCloud definition, is that comics are "sequential art"; the second, which I think of as the Pekar/Harvey definition, is that comics are "words and pictures"; the third, which I think of as the Horrocks/Campbell definition, is that comics can only be defined by what they historically have been, with a strong dose of "to hell with all this definition crap" mixed in in the bargain. As far as I'm concerned, all three have their merits; and one can most fruitfully engage with the field of comics by using, in various ways, all three.

The Codex is "new lit" by Eddie Campbell's definition -- a graphic novel but not comics (good enough for my purposes); this page, at least, is clearly comics in the Eisner/McCloud sense, even if the whole is not. But is this page comics under the Pekar/Harvey definition? Does an undecipherable alien script count as "words"? I shall argue in a moment (or have argued above, if you're reading the footnotes all together at the end) that the script is essential to the meaning (the feel, the effect, the nature...) of the Codex. But is it words? It's certainly supposed to make us think of words.)

*** Which is Eddie Campbell's basic point about the definitions, if I understand him properly.

**** An interesting test: can we think of this page -- page thirty-nine -- as not comics in the Eisner/McCloud sense? By this I mean: can we try not to process the images as a temporal (causal) sequence, showing us a location, a sequence of events, a use? Scott McCloud says that his iconic picture:

is comics if we read it as a man raising a hat -- but isn't if we read it as a picture of two men, one raising a hat. (Well, he says it of two squares. But you get my point.) But at any length, it becomes well-nigh impossible not to see most comics as sequential art -- not to do closure. Can we imagine an alien race alien enough to make a page like this and not intend sequence? (It's hard.)

Links to: an introduction to the series; an index of posts by creator; an index of posts by title.

When I began this series, I made a list of the first few entries I wanted to do and a large number of other works that I wanted to get around to eventually. But I always knew that happenstance would play a major part. In the case of the Codex Seraphinianus, created by Italian artist Luigi Serafini, the chance was my discovering (via Eddie Campbell) that it had been posted online, in its entirety, as a Flickr set.

I described the Codex in my earlier post, but to recap briefly: the Codex Seraphinianus is a fictional encyclopedia, presented as if it was an alien artifact: written entirely in an undecipherable alien script, with strange and hallucinogenic illustrations throughout the text giving glimpses of pregnant, elusive meaning. Whether it is supposed to be from an entirely alien world (in which case the obvious people sometimes included are puzzling), from an alien looking at our world (in which case the obviously fantastical lifeforms, places, etc, are puzzling), or something else, is unclear. It's a masterpiece of suggestive mystery, of meaningful nonsense. Like many people, I first heard of it from an off-hand comment in Douglas Hofstadter's Metamagical Themas; but until its recent posting I had only seen the various sample pages available here and there on the web, and had never read it in its entirety (as it is rare and quite expensive). Having actually read it, I knew I had to include a page in this series.

But have I in fact even read it now? In my earlier blog post about the Codex, I wondered whether the word "read" was the proper word to use in discussing it. I have looked at every page -- some for longer, some for less time: the text-only pages -- at a very rough guess, perhaps a fifth of the total -- are, obviously, particularly unrewarding; many of the heavily illustrated pages are so beautiful that they took my breath away. I have never used hallucinogens, but looking at the Codex makes me feel as if I know what LSD must be like. But have I read it? Is "read" the right word?

I have come to the conclusion that it is not. This is true even though I would without hesitation say I had "read" a silent comic like Peter Kuper's Sticks & Stones or Evan Drooker's Flood. The reason is that in the context of a work like the Codex, "read" implies something untrue -- that one has actually read the existent text and not simply looked at the images. Given that the text is, so far as anyone knows, nonsense (but see here), this is impossible; but to say, "I've read the Codex Seraphinianus" implies a mastery which is unwarranted. Further, while the pages are definitely better seen in sequence -- you get a lot more out of it approaching it as a whole work, with a given order,* than simply looking at any given sample pages (said the man writing a series of blog posts about pages taken out of context) -- you don't quite read the images the way that one "reads" (by which I mean something like "performs closure on", to use McCloud's term) silent comics. Say, therefore, that I have "looked through" the Codex: it will be more accurate.

In fact, since I have announced this as a series of great comics pages, including the Codex begs the question of whether it is comics or not. Now Eddie Campbell would argue vehemently that these categories are reductive: that one shouldn't care whether or not the Codex is comics -- one should simply care that it's good. And on many levels I agree with him. But since I disagree with him on equally many levels -- and since I don't want to try to weigh in on The Great Campbell/McCloud Debate™ now (though I may at some point in the future) -- I'll simply note that the page I'm discussing happens to be a page of comics, at least by the Eisner/McCloud definition of comics as "sequential art".** A few of the pages have sequences of art that are clearly meant to be read as temporal sequence -- i.e. are comics by the Eisner/McCloud definition -- but this page is rare in being dominated by a lengthy, comics-like sequence. I think the only other one laid out in quite so traditional a comics fashion is page 41 -- two pages later. (What that means I don't know, although the pages are thematically quite similar in a lot of ways.) So even if you won't call the Codex comics in its entirety -- and I pretty much wouldn't -- I think most people would agree that this page is comics.

Anyway, it's wonderful, and from a wonderful book, so bollocks to the definitions.***

So here is page 39:

I've rotated the image 90 degrees so that its (apparent, to us) proper orientation is up -- as one would, presumably, rotate the book if one shelled out the money to have a dead-tree copy in one's hands -- but if you want to see what it looks like in the book, click here.

In many ways, the "story" here is readily comprehensible -- although the story one gets out of it is distinctly surreal. In the first panel, we are shown a map (its status as a map made clear by the labeling, in the now-familiar alien script, which is on it); in the second through fifth panels we are shown rains, followed by the growth of some sort of crop; in the sixth panel, we see the crop harvested; in the seventh, we are shown in close-up what the crop is: ball-point pens, which grow in the manner of tubers; and in the final panel we are shown the use that these are put to: they are used as the components of necklaces.

(Page forty-one, which as I said is very similar in structure, shows the growth of chairs -- not as parts then manufactured, but as full chairs -- which are then sat on by (for some reason) someone wearing ice-skates.)

It's worth noting that this is hardly the strangest page in the book -- indeed, its very nature as comics makes it among the most straightforwardly comprehensible. Nevertheless, its combination of real and imaginary features, its reordering of the familiar world in a strange way, makes it (in many ways) quite typical of the Codex.

But what are we to make of this presentation? Is the Codex describing a world in which this actually takes place? Or is this the misinterpretation that an alien culture has of our world? Or is it supposed to be metaphorical -- about creation having its roots in the earth, and hanging like a chain about our necks? -- Further, is this an answerable question -- that is, if one studies the Codex for long enough, can one figure out where and when it is supposed to document? Or is it just an exercise in defamiliarization, a playful romp in the gardens of the strange? (If ever there's been an artistic object which aims for, and achieves, defamiliarization, it's the Codex Seraphinianus.) I don't know the answer to any of these questions: I enjoy the page as an exercise in dream-like strangeness, but I don't know what to make of it.

In discussion at Eddie Campbell's blog I said that the Codex as a whole reminded me of Jim Woodring's Frank, in its eerie, often-unsettling, dream-like (or hallucinogenic) tales which mix the familiar and the strange. A commentator, "John C" (who I think is the same John C who wrote perceptively about the Codex here) replied that he thought "it most closely resembles European fantasy works like those one sees from Roland Topor and various bande desinée artists rather than people like Jim Woodring." I'll stand by my Woodring thought, though I admit that it may well have as much to do with my limited frame of reference than anything else. (Jacek Yerka also strikes me as similar in spirit.) Overall, obviously, the dominant mode is surrealism; beyond that, I don't know.

Let me take one small topic: the alien script. What is it doing in this page? Well, it changes the viewpoint: it makes what we see a representative example rather than a specific incident. It implies a whole society -- that this is a tradition, a habit -- rather than, say, some strange specific incident in which pens happened to grow like tubers in the ground, and we had so many of them that we made necklaces. The script (along with the greater context) even helps establish a narrative voice -- one of detached description -- that we then read as the intent behind the pictures. We might be wrong about that voice: it's how encyclopedias that we know are written, and might not really apply to the Codex at all, given that its supposed to be alien. But I think we tend to impute that tone to the Codex, fairly or not. And, of course, once one thinks of the Codex as a product of an alien society, we realize that we are imputing to it all sorts of things that might be wrong: even the idea that the squiggles in question are a script (with an implied language and meaning behind them, even if we can't know them) -- and not, say, simply decoration, or their portraits of the strings of which matter is made -- is simply an assumption that may be wrong. The alienness of the Codex necessarily destabilizes all our attempts to bring meaning to it (although, at the same time, we can hardly help doing so.****) There's no question that the script is absolutely essential to the feel and nature and meaning (whatever that is) of the Codex -- even if we do skip by the all-text pages quickly (for what can one make of them?), their presence is important in helping shape the meaning of more heavily image-based pages such as page thirty-nine.

Surely it's important that this page (and its cousin, page forty-one) are in the "flora" section (again, see my first footnote below), which consists of drawings and sketches and diagrams and so forth of plants. It shapes how we feel about the page; but I don't think it makes it mean any one thing.

Is asking about its meaning just silly? Is it all just supposed to be beautiful and strange? Or, on the other hand, are we missing something big if we just groove on its strangeness rather than seek more specific meaning (it certainly seems set up to encourage us to do the latter).

Did I mention that the art is beautiful?

And what are we to make of the watch in the penultimate panel, the one where we see the man holding the tuber-pen out? That's a very modern-looking wrist-watch.

Is it comics? Have I read it? What does it mean? I don't know. But I know that it's wonderful. (Can I know that without knowing what it is or what it means? I think so, but it's a funny situation to be in.) Go take a look and see what you think.

Update: Nothing to do with the Codex, but Eddie Campbell (whose name I took in vain above) and I are hashing out issues of definition in the comments. Worth a look.

___________________________________

* The Codex is quite distinctly divided into eleven sections, each with a title page, introduction and table of some sort (a summary? a table of contents?) before the main matter. Further, the rough subject of each section is fairly clear (various different attempts to label the sections come out quite similarly). And each section gains in coherence if looked through all together in order -- although admittedly not by much.

** I think that there are three major definitions of comics/graphic novels in play right at the moment. The first, which I think of as the Eisner/McCloud definition, is that comics are "sequential art"; the second, which I think of as the Pekar/Harvey definition, is that comics are "words and pictures"; the third, which I think of as the Horrocks/Campbell definition, is that comics can only be defined by what they historically have been, with a strong dose of "to hell with all this definition crap" mixed in in the bargain. As far as I'm concerned, all three have their merits; and one can most fruitfully engage with the field of comics by using, in various ways, all three.

The Codex is "new lit" by Eddie Campbell's definition -- a graphic novel but not comics (good enough for my purposes); this page, at least, is clearly comics in the Eisner/McCloud sense, even if the whole is not. But is this page comics under the Pekar/Harvey definition? Does an undecipherable alien script count as "words"? I shall argue in a moment (or have argued above, if you're reading the footnotes all together at the end) that the script is essential to the meaning (the feel, the effect, the nature...) of the Codex. But is it words? It's certainly supposed to make us think of words.)

*** Which is Eddie Campbell's basic point about the definitions, if I understand him properly.

**** An interesting test: can we think of this page -- page thirty-nine -- as not comics in the Eisner/McCloud sense? By this I mean: can we try not to process the images as a temporal (causal) sequence, showing us a location, a sequence of events, a use? Scott McCloud says that his iconic picture:

is comics if we read it as a man raising a hat -- but isn't if we read it as a picture of two men, one raising a hat. (Well, he says it of two squares. But you get my point.) But at any length, it becomes well-nigh impossible not to see most comics as sequential art -- not to do closure. Can we imagine an alien race alien enough to make a page like this and not intend sequence? (It's hard.)

Thursday, March 29, 2007

Libertarianism in a Nutshell

Andrew Sullivan "fisks" David Brooks today. And in the course of so doing, he writes:

Of course, libertarians like to posture as people who always make the trade-off between government and liberty in favor of liberty. But it's a fundamentally dishonest posture: it's one that allows them to debate the question on their (imaginary) grounds, 'should we choose government or freedom', while avoiding the difficult question that everyone who is not an anarchist actually faces: what precisely should government do and not do? This is one of the (many) reasons why I don't agree with libertarian views; it is a rhetorical posture that hides the true issues. Thus, for example, for a generation Republicans have campaigned against taxes in a broad and general way. But only anarchists think there should be no taxes (since governments, like any other institution, require funding); but "what should we have government for, and how should we tax to pay for it?" is less rhetorically powerful.

But beneath this dishonesty -- one that Sullivan buys into, presumably because it is so common in libertarian rhetoric (I am not accusing him of deliberate dishonesty here) -- is another fundamental error: namely, the premise behind the libertarian posture, that "bigger government always means less personal liberty". Sullivan calls this "simply a fact"; but (in fact) it's not: it's a myth, and a pernicious one.

This is easiest to see when looking at the reductio ad absurdum of the claim -- which, as I already said, is anarchy. Anarchy does not produce more personal liberty: it produces (as we see to far too great an extent in the hell that is contemporary Iraq) far less of it. In an anarchy, people don't even have the freedom to walk down the street: because they will far-too-likely be kidnapped or killed. Anarchy produces only the freedoms to shiver in fear in a basement -- or to become a thug and gangster and try to out-kill and out-kidnap your rivals.

But if that's the easy case, the others are fairly easy too. Let's take Sullivan's economic generalization: "it is simply true that every dollar taken by the government is one dollar less for you and me to spend on what we decide is best." This would be true of the number of dollars were a fixed sum; but of course it isn't. It is often the case that the government will take a sum in taxes -- and use it to produce things that create far more economic growth than what was taken. (Roads are an obvious example here.) Thus people actually end up with a lot more money to spend on what they decide is best.

Or take Sullivan's second generalization: "every freedom removed or infringed by the government is one less for you and me to enjoy". This, too, is simply wrong. Here my favorite example (one due to Elizabeth Anderson (specifically here)) is traffic laws. Traffic laws restrict our liberty in specific circumstances in all sorts of ways -- we can't drive when sitting at a red light. But without them, all one gets is gridlock: as Anderson says, a situation in which we have "the formal freedom to choose any movement in one's opportunity set--which amounts to being able to rock forward and back a couple of inches from bumper to bumper, getting nowhere." Go read her post for a more extended version of the metaphor. The point is that government regulation can increase freedom as well as diminish it.

This isn't true of all government, of course. But that's why the fundamentally silly question of "more or less government" (or "bigger or smaller" government) should be set aside, and we should ask what policies produce the best outcomes: the freest, safest, richest society one can manage. And of course in that calculation there are trade-offs and mistakes. There are even some specific cases where a trade-off can be usefully analyzed as one between bigger government and more liberty (and far more cases which can be shoe-horned into that mold). But the idea that eliminating a government function always increases freedom is just silly.

To produce a just, safe, rich -- and, yes, free -- society, we need to get away from the silly abstract question of "how much government", and start thinking about the ways in which government can create a society which allows for the maximum possible freedom (and justice, safety and wealth -- since I don't think that freedom is the only virtue.) An less clownish version of libertarianism is one that argues that freedom is the only virtue that we should take seriously -- but which recognizes that government is sometimes essential to that freedom, and that lack of freedom can come from sources besides government. This would to my mind produce nightmarish results -- since, again, I don't think freedom is the only virtue worth pursuing; I think that justice and security and wealth have some value too.* But at least that sort of argument doesn't have a silly analysis of cause and effect at its base.

When speaking on specific issues libertarians often make extremely valuable contributions, reminding us of the importance of freedom and liberty as values to take into account. But their analysis of how to get there -- which is all to often 'less government', full stop -- is ridiculous as a general principle (even if, in some specific cases it will be right on the merits: some government programs reduce liberty and should as a consequence be scrapped. But that's as a result of specific, contingent factors and specific choices to be weighed and balanced -- not a general rule).

Sullivan's simple fact is not merely opinion: it's simply wrong. But it's too common a belief -- or at least rhetorical move -- in our political discourse. We need to get rid of it in order to think in a useful way about what sort of society we want, and how best to get there.

Update: Thanks to Andrew Sullivan for the link! And welcome, fellow Daily Dish readers. More in the sidebar if you're interested -- feel free to look around, kick off your shoes, stay awhile.

__________________________

* Here you get trade-offs -- although any 'more justice/security is less freedom' analysis will be just as simplistic as the 'more government is less freedom' analysis is -- and just as wrong.

But bigger government always means less personal liberty. This is simply a fact, not an opinion. The trade-off is always there. It may be worth it in some instances - which is why I'm not a libertarian. But it is simply true that every dollar taken by the government is one dollar less for you and me to spend on what we decide is best; every freedom removed or infringed by the government is one less for you and me to enjoy. You can defend the trade-off, and should at times, but please don't pretend it isn't there.Now of course Sullivan says he isn't a libertarian, because he thinks that the trade-off is sometimes worth it. This is based on a fundamentally false premise, however, because libertarians also 'think the trade-off is sometimes worth it'. Those who don't think the (supposed) "trade-off" is worth it -- that is, who think both that "bigger government always means less personal liberty" and that one should always decide on the side of smaller government/more personal liberty -- aren't libertarians at all: they're anarchists. This is the logical outcome: any given choice is between government and liberty; always choose liberty; no government is the obvious result.

Of course, libertarians like to posture as people who always make the trade-off between government and liberty in favor of liberty. But it's a fundamentally dishonest posture: it's one that allows them to debate the question on their (imaginary) grounds, 'should we choose government or freedom', while avoiding the difficult question that everyone who is not an anarchist actually faces: what precisely should government do and not do? This is one of the (many) reasons why I don't agree with libertarian views; it is a rhetorical posture that hides the true issues. Thus, for example, for a generation Republicans have campaigned against taxes in a broad and general way. But only anarchists think there should be no taxes (since governments, like any other institution, require funding); but "what should we have government for, and how should we tax to pay for it?" is less rhetorically powerful.

But beneath this dishonesty -- one that Sullivan buys into, presumably because it is so common in libertarian rhetoric (I am not accusing him of deliberate dishonesty here) -- is another fundamental error: namely, the premise behind the libertarian posture, that "bigger government always means less personal liberty". Sullivan calls this "simply a fact"; but (in fact) it's not: it's a myth, and a pernicious one.

This is easiest to see when looking at the reductio ad absurdum of the claim -- which, as I already said, is anarchy. Anarchy does not produce more personal liberty: it produces (as we see to far too great an extent in the hell that is contemporary Iraq) far less of it. In an anarchy, people don't even have the freedom to walk down the street: because they will far-too-likely be kidnapped or killed. Anarchy produces only the freedoms to shiver in fear in a basement -- or to become a thug and gangster and try to out-kill and out-kidnap your rivals.

But if that's the easy case, the others are fairly easy too. Let's take Sullivan's economic generalization: "it is simply true that every dollar taken by the government is one dollar less for you and me to spend on what we decide is best." This would be true of the number of dollars were a fixed sum; but of course it isn't. It is often the case that the government will take a sum in taxes -- and use it to produce things that create far more economic growth than what was taken. (Roads are an obvious example here.) Thus people actually end up with a lot more money to spend on what they decide is best.

Or take Sullivan's second generalization: "every freedom removed or infringed by the government is one less for you and me to enjoy". This, too, is simply wrong. Here my favorite example (one due to Elizabeth Anderson (specifically here)) is traffic laws. Traffic laws restrict our liberty in specific circumstances in all sorts of ways -- we can't drive when sitting at a red light. But without them, all one gets is gridlock: as Anderson says, a situation in which we have "the formal freedom to choose any movement in one's opportunity set--which amounts to being able to rock forward and back a couple of inches from bumper to bumper, getting nowhere." Go read her post for a more extended version of the metaphor. The point is that government regulation can increase freedom as well as diminish it.

This isn't true of all government, of course. But that's why the fundamentally silly question of "more or less government" (or "bigger or smaller" government) should be set aside, and we should ask what policies produce the best outcomes: the freest, safest, richest society one can manage. And of course in that calculation there are trade-offs and mistakes. There are even some specific cases where a trade-off can be usefully analyzed as one between bigger government and more liberty (and far more cases which can be shoe-horned into that mold). But the idea that eliminating a government function always increases freedom is just silly.

To produce a just, safe, rich -- and, yes, free -- society, we need to get away from the silly abstract question of "how much government", and start thinking about the ways in which government can create a society which allows for the maximum possible freedom (and justice, safety and wealth -- since I don't think that freedom is the only virtue.) An less clownish version of libertarianism is one that argues that freedom is the only virtue that we should take seriously -- but which recognizes that government is sometimes essential to that freedom, and that lack of freedom can come from sources besides government. This would to my mind produce nightmarish results -- since, again, I don't think freedom is the only virtue worth pursuing; I think that justice and security and wealth have some value too.* But at least that sort of argument doesn't have a silly analysis of cause and effect at its base.

When speaking on specific issues libertarians often make extremely valuable contributions, reminding us of the importance of freedom and liberty as values to take into account. But their analysis of how to get there -- which is all to often 'less government', full stop -- is ridiculous as a general principle (even if, in some specific cases it will be right on the merits: some government programs reduce liberty and should as a consequence be scrapped. But that's as a result of specific, contingent factors and specific choices to be weighed and balanced -- not a general rule).

Sullivan's simple fact is not merely opinion: it's simply wrong. But it's too common a belief -- or at least rhetorical move -- in our political discourse. We need to get rid of it in order to think in a useful way about what sort of society we want, and how best to get there.

Update: Thanks to Andrew Sullivan for the link! And welcome, fellow Daily Dish readers. More in the sidebar if you're interested -- feel free to look around, kick off your shoes, stay awhile.

__________________________

* Here you get trade-offs -- although any 'more justice/security is less freedom' analysis will be just as simplistic as the 'more government is less freedom' analysis is -- and just as wrong.

Sunday, March 25, 2007

Comic Book Thinking

Quoth the Rabbi (via):

Er, well, no, I guess not that one. Here's another!

Er, maybe not that one either. But surely this --

No, well, I guess not his comics either.

Maybe the Rabbi is reading the wrong comic books.

Religiously speaking, this is the belief that God gave freedom to all people made in His image, and that those who oppose freedom must be prepared to fight God.... It’s obvious to me that movies and comic books can make this case better than any subtle novel and more authentically than any spin-tested political speech. Comic books, and the graphic novels that evolved from them, are about the struggle of good against evil. Other art forms can make the claim that everything is gray, nothing is true, and nothing eternal. Of course these latter claims may be right, but if they are, then the age of heroes is over...Hmm, yes, the struggle against good and evil! Those who fight freedom fight God! The message of Graphic Novels! Yes of course. Like, for instance, this one:

Er, well, no, I guess not that one. Here's another!

Er, maybe not that one either. But surely this --

No, well, I guess not his comics either.

Maybe the Rabbi is reading the wrong comic books.

Saturday, March 24, 2007

100 Great Pages: Grant Morrison & Frank Quitely's We3 #2, pages 6-7

Fourth of a series of posts about 100 great comics pages.

Links to: an introduction to the series; an index of posts by creator; an index of posts by title.

Grant Morrison is widely regarded as one of the greatest of mainstream comics writers -- one of the few who might challenge Alan Moore for the slot of the single greatest mainstream comics writer ever. (Personally, I think Moore is clearly better; but Morrison is one of the few people for whom a case can be -- and often is is -- made.) Like Moore, Morrison has worked with many different artists in his career; but one of his most frequently collaborators has been Frank Quitely. Much of Morrison's best work has been with Quitely; indeed, comics scholar Geoff Klock has been recently arguing that in at least one case (Morrison's run on New X-Men) Morrison's work is variable in quality and is at its best with Quitely's collaboration. And the reverse is true too: Quitely, who is one of the very best mainstream comics artists working today, has done his best work with Morrison.

Morrison and Quitely's collaborations include (AFAIK this is a complete list (see update below)): Flex Mentallo (Morrison's sadly as-yet un-reprinted multiply metafictional masterpiece); JLA: Earth 2, a one-shot about the DC comics group; the very last issue of Morrison's long-running Vertigo series, The Invisibles; the currently ongoing series All-Star Superman; 10 issues of Morrison's 41-issue run on New X-Men; and, last but quite definitely not least, a short, three-issue series called We3, since published as a single graphic novel by Vertigo.

As that list indicates, Morrison often writes quite well-known superhero comics (Superman, X-Men, JLA); but We3, despite a few stylistic similarities, is not a superhero story: it's SF.* It's a story about three animals -- a dog, a cat and a rabbit -- who have been the subjects of an experiment to turn them into prototypes of a new sort of cyborg warrior. They are encased in battle armor, and they have been biologically altered in various ways -- for instance, their intelligence is enhanced, and they have (limited) speaking capabilities. And they are armed to the teeth. The graphic novel is about what happens when the three animals escape (with some assistance), and the agency responsible for their transformation goes after them.

As a story, We3 is comparatively straightforward, and is open to the charge of sentimentality about its animal protagonists. But it is extremely well told; grapples with the complex ethical issues of deadly warriors who are not themselves responsible for the fact that they are dangerous (and yet are no less dangerous for that); and, all in all, is a fun, gripping action-oriented SF story. Above all, in We3, Quitely's art is simply superb -- gorgeous, innovative and affecting. (Quitely's art is colored and digitally inked by Jamie Grant, who also deserves notice here. (The comic was lettered by Todd Klein, although I don't think we see an of his work in the page I'm going to discuss, as there isn't any dialog.))

The page I wish to discuss -- or pair of pages, if you prefer, since it is a two-page spread; but obviously it works as a single visual unit, and so I think it clearly counts as a page in some sense (including for the purposes of this series) -- is from an action sequence from early in issue 2,** in which the cyborg animals battle a team of soldiers who have been sent to hunt them down. Here's what it looks like:

The first impression from this two-page spread is of chaos: multiple fragmented panels, many overlapping; the superimposed figure of the cyborg dog on the top half of the page; the shifting viewpoints within the smaller panels. It's interesting, it's fresh; the question is, however, what's it doing? Is it just done differently to be cool?

And the answer is: no. It's that (and that's a good thing); but it's more than that, too.

There are, I believe, two possible interpretations of this page. Two pages before this sequence (#2, p. 4), one of the scientists responsible for changing the animals says of them "even their sense are different from ours. They're much faster than any human. They experience time and motion differently." So one might simply say that this is supposed to represent the view of the animals. But I don't think that's so. There's little in these pages to suggest that we are supposed to be seeing from the animals' viewpoint; in fact, in most views we're clearly not.

Rather, I think this page is a representation of the experience of battle: it's chaos, its speed, its gore and destructiveness and terror. And, yes, its excitement: even many soldiers who return from war disillusioned or as peace activists will admit to the power of the adrenaline surge that accompanies combat.

As it happens, the page is not quite as chaotic as it seems. If you take the time to read the sequence of panels carefully, you can see -- as Quitely himself says in this interview, "They actually do work in a sequence – there’re lots and lots there, so if you can be bothered, there’s stuff you can look at." The top row of what Quitely calls the "wee tiny" panels superimposed upon the larger one show, very clearly, the dog cyborg firing his built-in gun and a bullet hitting one of the soldiers in the eye. It's all in fragments: the tip of the weaponized limb, the bullet breaking the glass, a glob of blood. But it's perfectly comprehensible.

Similarly, all of the multiple, overlapping panels which are superimposed over the lower half of the page simply show the cat cyborg firing a bunch of spikes and piercing a few soldiers (you can tell its more than one because one has a beard and one does not), killing them quickly and terribly.) The fact that it's all in fragments, that the panels overlap and aren't in neat rows, is not simply visually striking (although it is that) -- not simply cool -- it also conveys something important: the experience of the battle. Superimposing multiple small panels over the large one give a sense of the speed of events that simply having them all in normal panel order would not (that would in fact make them seen drawn out, like slow-motion fights in films); having the panels overlap goes further and conveys the simultaneity (or near-simultaneity) of events. The partial images shown in the panels not only reflect the speed of events but also the fragmented comprehension that the men involved have of what is going on. Still, despite all of this, the sequence is comprehensible: if one takes the time (probably on a second or third reading) to slow down and put all the panels together, you can see that they make a coherent comics depiction of precisely what happens.

But, of course, that quote of Quitely's is followed by his line that "if you can’t be bothered, it’s simply carnage." And the point is that the page works on that level equally well. If you don't read all of the panels, you still get a key part of the experience, namely, the chaos and carnage and disorientation of a swift, deadly battle. The page represents the explosion of horror that happens the instant of the attack, erupting into the reader's view the moment the page is turned.

This is a great page because it is innovative comics: the shifting viewpoints, the reliance on what Scott McCloud would call aspect-to-aspect panel transition, the juxtaposition of small and large panels, etc, is all formally innovative (at least for Western comics: Morrison has said that part of what he was trying to do with We3 was to create "western manga", and certainly many of the techniques he and Quitely used had lots of precedent there (which is not to say that they didn't use them in innovative ways.)) But at the same time, the innovations are put to a crucial storytelling use: to conveying the nature of battle, the horror and the confusion and the excitement of it. This page (like much of We3) is an action sequence, solidly within the tradition thereof -- while at the same time being visually new and fresh (much like The Matrix in film). It takes an old idea -- a battle scene -- and makes it new again: closer to reality, more visually interesting, and still exciting. It can be read slowly, or glimpsed in an instant, and works at both speeds.

All of which makes it a great page. And if you like it, I suggest picking up a copy of We3, because chances are you'll like the rest of it too.

Update: Turns out that list of Morrison/Quitely collaborations was almost complete. Geoff Klock notes a Quitely interview where he mentions the one left off the list, a 9-page story called "New Toys" in Weird War Tales #3.

__________________________________

* This is off topic, but while the superhero genre is often discussed as if it's a sub-genre of fantasy (or occasionally SF), I think this is misleading; I think the genres are related in much the same way that horror and fantasy are related. A lot of horror has elements of fantasy, and some of it is inarguably fantasy; but it is also its own genre, with its own history, traditions, deviations, models and so forth. The same, I would argue, is true for the superhero genre.

** I'd prefer to give its page number in the trade paperback, since that's how I read the series -- but the paperback has no page numbers, and it's simplier to just count pages within each chapter (issue). So it's issue #2, pages 6-7.

Links to: an introduction to the series; an index of posts by creator; an index of posts by title.

Grant Morrison is widely regarded as one of the greatest of mainstream comics writers -- one of the few who might challenge Alan Moore for the slot of the single greatest mainstream comics writer ever. (Personally, I think Moore is clearly better; but Morrison is one of the few people for whom a case can be -- and often is is -- made.) Like Moore, Morrison has worked with many different artists in his career; but one of his most frequently collaborators has been Frank Quitely. Much of Morrison's best work has been with Quitely; indeed, comics scholar Geoff Klock has been recently arguing that in at least one case (Morrison's run on New X-Men) Morrison's work is variable in quality and is at its best with Quitely's collaboration. And the reverse is true too: Quitely, who is one of the very best mainstream comics artists working today, has done his best work with Morrison.

Morrison and Quitely's collaborations include (AFAIK this is a complete list (see update below)): Flex Mentallo (Morrison's sadly as-yet un-reprinted multiply metafictional masterpiece); JLA: Earth 2, a one-shot about the DC comics group; the very last issue of Morrison's long-running Vertigo series, The Invisibles; the currently ongoing series All-Star Superman; 10 issues of Morrison's 41-issue run on New X-Men; and, last but quite definitely not least, a short, three-issue series called We3, since published as a single graphic novel by Vertigo.

As that list indicates, Morrison often writes quite well-known superhero comics (Superman, X-Men, JLA); but We3, despite a few stylistic similarities, is not a superhero story: it's SF.* It's a story about three animals -- a dog, a cat and a rabbit -- who have been the subjects of an experiment to turn them into prototypes of a new sort of cyborg warrior. They are encased in battle armor, and they have been biologically altered in various ways -- for instance, their intelligence is enhanced, and they have (limited) speaking capabilities. And they are armed to the teeth. The graphic novel is about what happens when the three animals escape (with some assistance), and the agency responsible for their transformation goes after them.

As a story, We3 is comparatively straightforward, and is open to the charge of sentimentality about its animal protagonists. But it is extremely well told; grapples with the complex ethical issues of deadly warriors who are not themselves responsible for the fact that they are dangerous (and yet are no less dangerous for that); and, all in all, is a fun, gripping action-oriented SF story. Above all, in We3, Quitely's art is simply superb -- gorgeous, innovative and affecting. (Quitely's art is colored and digitally inked by Jamie Grant, who also deserves notice here. (The comic was lettered by Todd Klein, although I don't think we see an of his work in the page I'm going to discuss, as there isn't any dialog.))

The page I wish to discuss -- or pair of pages, if you prefer, since it is a two-page spread; but obviously it works as a single visual unit, and so I think it clearly counts as a page in some sense (including for the purposes of this series) -- is from an action sequence from early in issue 2,** in which the cyborg animals battle a team of soldiers who have been sent to hunt them down. Here's what it looks like:

The first impression from this two-page spread is of chaos: multiple fragmented panels, many overlapping; the superimposed figure of the cyborg dog on the top half of the page; the shifting viewpoints within the smaller panels. It's interesting, it's fresh; the question is, however, what's it doing? Is it just done differently to be cool?

And the answer is: no. It's that (and that's a good thing); but it's more than that, too.

There are, I believe, two possible interpretations of this page. Two pages before this sequence (#2, p. 4), one of the scientists responsible for changing the animals says of them "even their sense are different from ours. They're much faster than any human. They experience time and motion differently." So one might simply say that this is supposed to represent the view of the animals. But I don't think that's so. There's little in these pages to suggest that we are supposed to be seeing from the animals' viewpoint; in fact, in most views we're clearly not.

Rather, I think this page is a representation of the experience of battle: it's chaos, its speed, its gore and destructiveness and terror. And, yes, its excitement: even many soldiers who return from war disillusioned or as peace activists will admit to the power of the adrenaline surge that accompanies combat.

As it happens, the page is not quite as chaotic as it seems. If you take the time to read the sequence of panels carefully, you can see -- as Quitely himself says in this interview, "They actually do work in a sequence – there’re lots and lots there, so if you can be bothered, there’s stuff you can look at." The top row of what Quitely calls the "wee tiny" panels superimposed upon the larger one show, very clearly, the dog cyborg firing his built-in gun and a bullet hitting one of the soldiers in the eye. It's all in fragments: the tip of the weaponized limb, the bullet breaking the glass, a glob of blood. But it's perfectly comprehensible.

Similarly, all of the multiple, overlapping panels which are superimposed over the lower half of the page simply show the cat cyborg firing a bunch of spikes and piercing a few soldiers (you can tell its more than one because one has a beard and one does not), killing them quickly and terribly.) The fact that it's all in fragments, that the panels overlap and aren't in neat rows, is not simply visually striking (although it is that) -- not simply cool -- it also conveys something important: the experience of the battle. Superimposing multiple small panels over the large one give a sense of the speed of events that simply having them all in normal panel order would not (that would in fact make them seen drawn out, like slow-motion fights in films); having the panels overlap goes further and conveys the simultaneity (or near-simultaneity) of events. The partial images shown in the panels not only reflect the speed of events but also the fragmented comprehension that the men involved have of what is going on. Still, despite all of this, the sequence is comprehensible: if one takes the time (probably on a second or third reading) to slow down and put all the panels together, you can see that they make a coherent comics depiction of precisely what happens.

But, of course, that quote of Quitely's is followed by his line that "if you can’t be bothered, it’s simply carnage." And the point is that the page works on that level equally well. If you don't read all of the panels, you still get a key part of the experience, namely, the chaos and carnage and disorientation of a swift, deadly battle. The page represents the explosion of horror that happens the instant of the attack, erupting into the reader's view the moment the page is turned.

This is a great page because it is innovative comics: the shifting viewpoints, the reliance on what Scott McCloud would call aspect-to-aspect panel transition, the juxtaposition of small and large panels, etc, is all formally innovative (at least for Western comics: Morrison has said that part of what he was trying to do with We3 was to create "western manga", and certainly many of the techniques he and Quitely used had lots of precedent there (which is not to say that they didn't use them in innovative ways.)) But at the same time, the innovations are put to a crucial storytelling use: to conveying the nature of battle, the horror and the confusion and the excitement of it. This page (like much of We3) is an action sequence, solidly within the tradition thereof -- while at the same time being visually new and fresh (much like The Matrix in film). It takes an old idea -- a battle scene -- and makes it new again: closer to reality, more visually interesting, and still exciting. It can be read slowly, or glimpsed in an instant, and works at both speeds.

All of which makes it a great page. And if you like it, I suggest picking up a copy of We3, because chances are you'll like the rest of it too.

Update: Turns out that list of Morrison/Quitely collaborations was almost complete. Geoff Klock notes a Quitely interview where he mentions the one left off the list, a 9-page story called "New Toys" in Weird War Tales #3.

__________________________________

* This is off topic, but while the superhero genre is often discussed as if it's a sub-genre of fantasy (or occasionally SF), I think this is misleading; I think the genres are related in much the same way that horror and fantasy are related. A lot of horror has elements of fantasy, and some of it is inarguably fantasy; but it is also its own genre, with its own history, traditions, deviations, models and so forth. The same, I would argue, is true for the superhero genre.

** I'd prefer to give its page number in the trade paperback, since that's how I read the series -- but the paperback has no page numbers, and it's simplier to just count pages within each chapter (issue). So it's issue #2, pages 6-7.

Thursday, March 22, 2007

The Weirdest Book in the World is (Temporarily?) Online

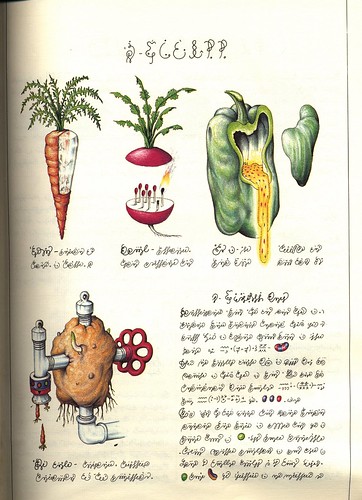

Via Eddie Campbell, I see that Italian artist Luigi Serafini's Codex Seraphinianus has been posted, in its entirety, as a series of flickr images.* The Codex Seraphinianus presents as an Encyclopedia from an alien culture -- written entirely in an invented script (nonsense, or possibly a whole invented language -- I don't think that anyone knows), with images, charts, etc. It's as if an actual alien artifact was simply dropped into our world.

I've read about it many times before, but I've never actually read it previously -- only a handful of sample pages that various online sites (see links earlier in this sentence) have. (Is "read" really the operative verb here? I'm emphatic in my belief that one "reads" even wordless comics, but I'm not sure if it applies to the Codex.) The reason, straightforwardly, is that the book is extraordinarily expensive -- many hundreds of dollars for most editions -- and hard to find in libraries (Cornell has one, but they keep it in their "rare book and manuscript" archives so you can't actually check it out). But now, hey presto, it's online.

Just so you get a sense of what I'm talking about, here's a page which is (I believe) reasonably representative of the idea -- page 31:

It's an extraordinary artistic creation -- a piece of art that really fits into no medium that I know of (I guess "artist's books" is the closest I can think of), one so weird that one hardly knows how to approach it. But that's exactly why it's cool.

But given our current era of The Copyright Wars™, Lord knows how long it'll stay online, though, so if you're at all interested I strongly recommend you go check it out sooner rather than later.

Postscript: ... Okay, in one sense the title of this blog post is untrue: the Codex Seraphinianus is online, but it isn't the weirdest book in the world. At best it's the second weirdest. The weirdest book in the world is probably the Voynich Manuscript -- which I believe was an inspiration for the Codex, although I'm not sure about that -- which is a lot like the Codex, except that in the case of the Voynich no one knows who created it, which frankly makes it even weirder. I mean, ultimately, we know that the Codex is an artist's project. The Voynich manuscript may be one... or it may be a real encyclopedia in some sort of code... or it may be something else. We don't know. From what I've seen of it, it's not quite as beautiful as the Codex, but it's almost certainly weirder. (On the other hand, it too is online -- see the last link on this page for more info, since it's not as simple as just a Flickr set -- so I guess the blog post title is true either way.) Update: Via BoingBoing, the Voynich manuscript is now also available as a Flickr set. I haven't looked carefully, but it definitely doesn't look as cool as the Codex based on a quick glance. BoingBoing also notes a new statistical analysis indicating that the Voynich manuscript may be a hoax.

Update: I've written another post about the Codex which you can find here.

______________________________

* By the way, is it me, or has Flickr just gotten worse after its recent merging with Yahoo?

I've read about it many times before, but I've never actually read it previously -- only a handful of sample pages that various online sites (see links earlier in this sentence) have. (Is "read" really the operative verb here? I'm emphatic in my belief that one "reads" even wordless comics, but I'm not sure if it applies to the Codex.) The reason, straightforwardly, is that the book is extraordinarily expensive -- many hundreds of dollars for most editions -- and hard to find in libraries (Cornell has one, but they keep it in their "rare book and manuscript" archives so you can't actually check it out). But now, hey presto, it's online.

Just so you get a sense of what I'm talking about, here's a page which is (I believe) reasonably representative of the idea -- page 31:

It's an extraordinary artistic creation -- a piece of art that really fits into no medium that I know of (I guess "artist's books" is the closest I can think of), one so weird that one hardly knows how to approach it. But that's exactly why it's cool.

But given our current era of The Copyright Wars™, Lord knows how long it'll stay online, though, so if you're at all interested I strongly recommend you go check it out sooner rather than later.

Postscript: ... Okay, in one sense the title of this blog post is untrue: the Codex Seraphinianus is online, but it isn't the weirdest book in the world. At best it's the second weirdest. The weirdest book in the world is probably the Voynich Manuscript -- which I believe was an inspiration for the Codex, although I'm not sure about that -- which is a lot like the Codex, except that in the case of the Voynich no one knows who created it, which frankly makes it even weirder. I mean, ultimately, we know that the Codex is an artist's project. The Voynich manuscript may be one... or it may be a real encyclopedia in some sort of code... or it may be something else. We don't know. From what I've seen of it, it's not quite as beautiful as the Codex, but it's almost certainly weirder. (On the other hand, it too is online -- see the last link on this page for more info, since it's not as simple as just a Flickr set -- so I guess the blog post title is true either way.) Update: Via BoingBoing, the Voynich manuscript is now also available as a Flickr set. I haven't looked carefully, but it definitely doesn't look as cool as the Codex based on a quick glance. BoingBoing also notes a new statistical analysis indicating that the Voynich manuscript may be a hoax.

Update: I've written another post about the Codex which you can find here.

______________________________

* By the way, is it me, or has Flickr just gotten worse after its recent merging with Yahoo?

Sunday, March 18, 2007

Rilstone on Jackson on Tolkien

Andrew Rilstone, who by all appearances is a Tolkien geek of major proportions, wrote a whole lot of reviews of Peter Jackson's Lord of the Ring films. I don't always agree with him -- in some places I liked the films more/thought they worked better/thought he was being too harsh, and in some places I liked them less/thought they worked less well/thought he wasn't being harsh enough -- but he's got a very interesting take on them. Even better, he has a very funny take on them. (He is increasingly funny as he goes on, getting increasingly bitter about the films.)

The funniest (and the least forgiving to Jackson) is this 2004 talk entitled "Go Away and Never Come Back", written after he'd seen the whole trilogy. If you like that (or if you're mad at him for being too harsh and want a bit more nuance), you can go read the rest of his reviews which were done in real time (as it were), as he watched each film: The Fellowship of the Ring (probably the most forgiving to Jackson (probably justifiably)); The Two Towers; the five appendixes to his Two Tower review (a Tolkien geek for sure (they include good material, though)); Return of the King parts one, two, three, four (all very short save for three) and lastly his review of the Extended DVD edition of the Return of the King.

As I said: I think he is both too nice and too harsh at times. But he's interesting, and he's funny. Have a look -- at least at the "Go Away" one (which is one of the last written, I think).

As for me, if I didn't have to teach in nine hours, I'd go procrastinate further by reading him on Star Wars...

Update: For another mixed -- but ultimately far more positive -- view of Jackson's films by one well versed in their Tolkien, I recommend Tom Shippey's essay "Another Road to Middle Earth" in the anthology Understanding the Lord of the Rings: the Best of Tolkien Criticism. Shippey is an extremely interesting reader of Tolkien (I highly recommend his book The Road to Middle Earth for anyone looking for a book-length work on Tolkien), and so it's very interesting to get his perspective on the films.

Long-later update: Sadly, Rilstone seems to have let his site lapse. So, for convenience, here are links to Rilstone's essays on the films on wayback machine: Fellowship; Two Towers; Return of the King (also 1, 3, 4); Go Away and Never Come Back; and the Extended DVD.

The funniest (and the least forgiving to Jackson) is this 2004 talk entitled "Go Away and Never Come Back", written after he'd seen the whole trilogy. If you like that (or if you're mad at him for being too harsh and want a bit more nuance), you can go read the rest of his reviews which were done in real time (as it were), as he watched each film: The Fellowship of the Ring (probably the most forgiving to Jackson (probably justifiably)); The Two Towers; the five appendixes to his Two Tower review (a Tolkien geek for sure (they include good material, though)); Return of the King parts one, two, three, four (all very short save for three) and lastly his review of the Extended DVD edition of the Return of the King.

As I said: I think he is both too nice and too harsh at times. But he's interesting, and he's funny. Have a look -- at least at the "Go Away" one (which is one of the last written, I think).

As for me, if I didn't have to teach in nine hours, I'd go procrastinate further by reading him on Star Wars...

Update: For another mixed -- but ultimately far more positive -- view of Jackson's films by one well versed in their Tolkien, I recommend Tom Shippey's essay "Another Road to Middle Earth" in the anthology Understanding the Lord of the Rings: the Best of Tolkien Criticism. Shippey is an extremely interesting reader of Tolkien (I highly recommend his book The Road to Middle Earth for anyone looking for a book-length work on Tolkien), and so it's very interesting to get his perspective on the films.

Long-later update: Sadly, Rilstone seems to have let his site lapse. So, for convenience, here are links to Rilstone's essays on the films on wayback machine: Fellowship; Two Towers; Return of the King (also 1, 3, 4); Go Away and Never Come Back; and the Extended DVD.

Saturday, March 17, 2007

100 Great Pages: R. Crumb's "Short History of America", Page 4

Third of a series of posts about 100 great comics pages.

Links to: an introduction to the series; an index of posts by creator; an index of posts by title.

The difficulty here is deciding what counts as a 'page'. This 12-panel work has been presented in many different formats: you can buy it from the official Crumb site as a single-page poster; it was likewise presented as a single page in The Complete Crumb Volume 17 (at a size so small as to be nearly illegible); several web sites have presented it as an animation; the Guardian presented it in two parts; and so forth. (A related difficulty is that there seem to be two versions, both color and black and white -- both done by Crumb, so far as I can tell.)

Frankly, a good argument could be made that Crumb's "Short History of America" is one of those comics for which 'page' is not the relevant unit of analysis, and thus ineligible for this series.

But in the early stages of thinking about this series, I happened to check out Ivan Brunetti's Anthology of Graphic Fiction, Cartoons, and True Stories, in which this work (along with a very generous selection of other Crumb works, both on his own and in collaboration with Harvey Pekar) is presented. (I didn't check, but it looks to me like more Crumb is included than any other single artist.) I'd read it before -- heck, I even had the images saved on my computer -- but as sometimes happens when re-encountering great art, seeing the work in Brunetti's book made me see as if for the first time how amazing it was. (Partly this was because Brunetti's book was the first time I had ever seen the work in print, and the details of the work were simply so much clearer on a high-resolution, dead-tree screen -- and more than in any other comics I can think of, in this piece it is the details that make the work.) And so I decided that a page of this work had to be included in my hundred. And Brunetti presented the comic as a four-page work.

For that matter, there really wasn't any doubt in my mind about which page, either: it was page four. Amazing as the whole work is, it was page four that took my breath away.

It is most effective in context, however, so let me link to a few versions of the entire work. Here's all twelve panels in black and white; here are the first six panels in color (and then here are the second six). Here's a version done up as an animation, although I personally don't like that nearly as well.

If you've never seen Crumb's work before, incidentally, this is a good piece to serve as an introduction to Crumb for a number of reasons. Crumb is, by almost universal acclaim, one of the great draftsmen of his age. One aspect of his superb drawing is his drawing of the urban landscape -- which is, of course, highlighted in this piece. Crumb has a certain reputation as a social critic, too, and that is also featured at its best here.

At the same time, most of the less universally liked aspects of Crumb's work are absent. While he is not as blatantly or over-the-topic misogynistic as fellow cartoonist Dave Sim, Crumb has often, and I think justifiably, been called misogynistic. I don't know enough about his work to evaluate the charges of racism that are often hurled -- the defense is basically that Crumb isn't racist so much as misanthropic, and that reveals itself in the way he portrays everybody -- but it's there. Frankly, much as I like Crumb's drawing, I'm not crazy about his writing.

(Fortunately for those of us who feel this way, Crumb has done a fair amount of work in collaboration. He's illustrated a lot of scripts for autobiographical comics writer Harvey Pekar -- all but the most recent ones are collected in the 1996 collection Bob and Harv's Comics -- and if you don't like Crumb's writing, that's a good book to read. He's also illustrated a number of Kafka stories in R. Crumb's Kafka (first published under the title Introducing Kafka). And various of his other works tell other people's stories and thus are fairly free of (what some people see as) the pernicious elements of Crumb's work; for instance, I recommend his eight-page retelling of "The Religious Experiences of Philip K. Dick")

At any rate, "A Short History of America", despite being written* as well as drawn by Crumb, contains most of his virtues and few of his defects. And it's short, and online, so go read it**.

And now, here's page four:

The page is beautifully drawn -- each picture is just an incredible example of draftsmanship. Crumb is a superb artist, and this is a great example of it.

But what's really astonishing here are the details -- the precise eye for the details of historical change, the slow evolution of the urban environment. Note the trolley in the top panel and the bus (not a trolley) in the second panel -- along with the bus stop sign added on the central post in the middle of the picture; and then, of course, there's the lack of any public transit in the final panel (although the there's still the bus stop sign). Note the changing styles of the cars; the changing style in the traffic light between panels two and three. Note the Texaco station becoming a stop and shop. Look at the factory in the right background being replaced by the "Greenwood Village" (what a great name!) housing. Notice the newspaper box in just the middle panel. (The one detail I don't quite get is the disappearance of the stop sign from the top to the middle panel -- why wouldn't there still be one?)